Although the large Spring Number is not with us, we are

attempting once more to produce a twelve page B.B. This month, we take

advantage of this increase in size to print a long article taking up most of

the B.B. To these of you who are not

interested in cave surveying, we apologise and hope that the next time we print

an equally long article, it will be on a subject you are interested in (within

reasonable limits, of course!)

This article, as well as being long, is of a controversial

nature, as it suggests a modification, to a well established practice. Whenever the B.B. has printed articles which

were felt to contain some controversial elements in the past, these have always

performed like damp squibs, and not raised a single voice of agreement or

dissent. We hope that, in this case, we

shall get some correspondence agreeing

or disagreeing with the article, as the

subject of cave surveying is one in which there may well be considerable scope

for new ideas.

“Alfie”

Notice

Whitsun weekend. There will be a club meet at Gaping Ghyll. A coach is being arranged by Brian

Prewer. Anyone interested should get in

touch as early as possible. It was

suggested that the club should visit Lancaster Pot, but this has proved

impossible owing to the grouse season, approximate cost 35/-. Date June 10th.

Some (Controversial?) Thoughts on Cave Survey Gradings.

by Bryan Ellis

This article in no way tells you how to make a cave

survey. It deals only with one aspect of

the completed survey that of applying; a grading of expected accuracy. It is important to remember that the views

expressed are solely, as far as I know, those of the author and must not be

taken as representative of those of the B.E.C. committee, nor of the editor,

nor of any other member. The purpose is

to express on paper some of the views of the author in the hope that they will

provoke discussion. Now that you have

been warned, here goes.

Some form of survey grading is very desirable so that, by

simply looking at this figure, the reader may make a reasonably reliable

estimate of the accuracy to be expected. However, at the same time it is even better if accompanying each cave

survey published there is an article describing the instruments used in making

the survey; how the figures are calculated and the survey plotted; a list of

known closure errors and so on.

Let us take four hypothetical cave surveys, those of

Axbridge Hole; Burrington Cavern; Cheddar Sleeker and Draycott Swallet. A beautifully produced survey of Axbridge

Hole is published without any accompanying screed! The survey looks very good but even the

closest examination fails to reveal any sign of a grading. It is therefore impossible to arrive at any

estimate of its accuracy. It is hardly

likely that a survey would be produced

as elaborately as this for anything less than a Cave Research Group grading of

5, but one cannot be sure. Perhaps I may

know the surveyor and therefore know the instruments that he uses and can guess

that the accuracy is perhaps between the grades of 5 and 6. But this is only guesswork and if I don’t

know him, I would have no idea at all.

Our second hypothetical survey has been published, in a club

journal; this of Burrington Cavern. Once

again, close scrutiny of the map fails to show any sign of a grading. This time, however, the situation is much

better because there is an excellent article by the surveyor accompanying the

survey. This article describes in great

detail the instruments that were used, the way in which he made the survey,

calculated the position of each station – and he also gives a table of known

closure errors. This article is a model

of what such an article should be except that even in the text there is no

indication of the grading claimed. Possibly

the idea is that, by giving the reader all the details, he should be left to

form his own conclusion, but before he can do so he must read all through the

text. He can get no idea from the survey

itself. Furthermore, the surveyor

himself is the best judge of the accuracy to be expected and if he gives an

opinion then perhaps the reader may like to adjust it slightly after reading

the text.

The third survey is of a cave known as Cheddar Slocker and,

like the first, is a well produced sheet but without any accompanying

description. This time, examination of

the survey shows that the surveyor has claimed a grading if 5. Anyone looking at this map now knows that, as

a minimum, a calibrated prismatic compass; metallic tape and a clinometer were

used. It is therefore safe to assume

that the survey is accurate enough for most purposes. However, as there is no accompanying article,

there is nowhere to state what instruments actually were used, nor of the

closure errors that were found in the closed traverses in the cave.

Finally, we can consider the survey of Draycott Swallet, our

final hypothetical survey. This survey

has been published in similar form to those of Axbridge Hole and Cheddar

Slocker, but this time it has been sold together with a small booklet. On the sheet is found the grading claimed by

the surveyor and therefore an estimate of accuracy can be made

immediately. In the booklet are found

all the details of the survey and its making, so if anyone is interested, they

can read through it and then they should have an even better idea of the

accuracy of the survey.

The idea of quoting at length the details of these surveys

is to give the reader an idea of why I consider both a grading and an

accompanying screed to be the ideal. The

grading on the survey is a quick reference guide and the article gives

greater details.

Mention has already been made on several occasions of the

grading. I have stated why I consider

one to be necessary (yes, the word ‘necessary’ is purposely used instead of

merely ‘desirable’) but on what are these gradings going to be based? If it

were possible, then the ideal would be a grading based on the known accuracy of

the survey. However, this is very

rarely, if ever, known and therefore some other method must be used. In many surveys there are closed traverses

and it could be assumed that the closure errors on these loops are

representative of the whole survey. The

total probable error of the survey could then be determined and the grading

based on this figure. This system would

be satisfactory if every survey contained a closed traverse but many do not,

especially surveys of individual passages such as those produced of new

extensions to caves. This system cannot

therefore be used unless one is going to have one system for those surveys including a closed traverse and

another for those that do not. This

would be most undesirable.

Another basis on which an estimate of accuracy can be based

is, on the instruments that are used and the accuracy with which they are read. The assumption of which this system is based is not ideal because

the accuracy attained with the same

instruments used by different surveyors will vary as also will the results by

the same surveyor under different caving conditions. Despite this, a fairly simple system of

grading can be devised that will give an indication of the accuracy to be

expected.

In 1960, the Cave Research Group of

published a paper on cave surveying by A.L. Butcher and this included a system

of survey grading recommended by the C.R.G. This system is based on the instruments used, and has been repeated in ‘British Caving.’ It is, in my opinion, far from ideal but, as

it has been given national publication and is used by practically all cave

surveyors it should not be changed now unless anyone can design the perfect

answer. Not agreeing with the Cave

Research Group (and many Mendip cavers do not) is not an excuse for trying to

replace the present system by one that is only slightly better, if at all.

Having said that the present system is not ideal I should be

Having said that the present system is not ideal I should be

more explicit and give my reasons for saying this, my main criticism of the

C.R.G. gradings is that it appear to have been designed for specific

combinations of instruments, and there is no way of arriving at a grading if a

different combination is used other than be guessing at the equivalent degree

of accuracy. Partly following from this

criticism is my second, that there is no provision for using any form of

clinometer to measure slopes until one reaches grade 5. Figure 1 shows the percentage error that

occurs in a plan if the angle of inclination is ignored and it will be seen

that a slope of 8o introduces an error of 1% while a slope of 16o gives an

error of 4%. As the angle increases, the

error increases even more so, and with an angle of 25° there is a 10%

error. This should show the importance

of slope when making a cave survey of any reasonable accuracy. Even with roughly measured plans of approx.

grade 3, it is often useful to take readings of slope, but no credit can be

taken for the increased accuracy obtained when using the present C.R.G.

System. If it intended to produce a

section as well as a plan, then it is important that angles of inclination

should be measured. Figure 2 shows the

changes in height (for various angles of inclination) that are not going to be

recorded if no account is taken of slope. For a cave 1,000 feet long, and having an average slope of 10o, a

vertical change of 175 feet will be lost. My own experience of cave surveying has shown me that it is extremely

difficult to estimate angles in a vertical plane with any accuracy, and this

has been borne out by tests on other people. For this reason, it is most desirable to measure angles of slope and not

estimate them. A slope of 5o will not be

noticed normally in a cave and while it will introduce an error of half a

percent in the plan, three feet will have been lost, in the section with a

survey leg of thirty feet.

During the year, the Northern Cavern and Mine Research

Society published their own grade of survey. This is just a single grade, approximately equivalent to C.R.G. grade 6,

to which they intend making all their surveys. The amazing thing about this grade is, that while they intend to use a

tripod mounted prismatic compass marked in half degrees and read to one sixth

of a degree, they only consider desirable and not essential, the use of some

form of clinometer. They aim always to

measure horizontal distances, to the nearest inch, and then calculate the

co-ordinates of their stations using five or seven figure logarithms. In my opinion, some of these measurements,

and the calculations, are going to be considerably more accurate than others

and the resulting survey is going to have a far greater error than they intend.

![]()

Having made criticisms of the C.R.G. system of grading, can

Having made criticisms of the C.R.G. system of grading, can

any improvements be suggested? I

made the criticisms and therefore I

will give my suggested modification of the scheme. My aim is to make the scheme less specific in the instruments to

be used for the survey so that a grading can be obtained, without guesswork,

when using a combination of instruments other than one of those listed by Butcher. It also decreases the guesswork when arriving

at a grading after’ using an instrument not included in my list, because the instruments are listed in order

of increasing accuracy and because the accuracy of the instruments are

sometimes given.

In table 1 will be found a list of instru¬ments, and other

means most likely to be used when making a cave survey, and alongside each is

given a number. The scheme simply

consists of adding together the numbers shown against each instrument that was

used in making the survey, and the result is then that of the cave survey. One feature of this scheme is that the

surveyor is allowed to increase or decrease the final grading, thus obtained

by half a grade. This is to take into

account factors which cannot easily be written down as hard and fast rules;

such factors as the care, with which the surveyor made his instrument readings;

the conditions under which these

readings were made; known closure errors, etc. In other words this allows the surveyor latitude to alter the grading

slightly either way depending on how accurate he feels the survey should be.

Another feature is the increasing of a grading by half a

grade if the ‘leap-frog’ method is used with hand held instruments. In this method, the surveyor, instated of

starting at Station 1, taking, readings to Station 2, then moving to 2 and taking readings to 3

etc, starts at Station 2, takes readings

to 1 and 3, then moves to 4 and takes

readings to 3 and 5, and so on.

A couple of examples should remove any doubts about the

working of the scheme. Thus, a survey is

made using a metal tape and a calibrated compass and a clinometer both mounted

on tripods and the readings being

accurate to + or – half a degree, then the numbers are 2 + 4 = 6 and a grading

of 5-5 to 6.5 could be claimed. As

another example, if to make a survey a cloth tape; a hand held, prismatic

compass and a hand held clinometer (both accurate to + pr – 1o) were used, then

the grading would be 1.75 + 1.75 + 1.25 which gives a total of 4.75. As it is not intended that survey gradings

should be given other than as whole or half numbers, then the surveyor would

claim either 4.5 or 5 depending on whether or not he thought the survey was as

accurate as possible with the instruments used.

It will be found that, in most cases, the gradings obtained

with, this scheme agrees with those given against the examples listed on page

393 of British Caving. The main

variations occur round the original gradings of 4 and 5. As already in intimated, the author has

always thought that the difference between these two gradings is very wide; not only does one

have to use a calibrated compass to increase from grade 4 to grade 5, but a clinometer must also be used,

and this can lead to a very great increase in accuracy.

Table 2 shows a comparison of gradings between the examples

given in British Caving and the gradings that are attained by this

scheme. It will be seen that the

maximum, grading on this system is 7.5 as compared with a C.R.G. maximum of

7. However, it is extremely unlikely

that anyone making a cave survey with the instruments required for the maximum

grading would at the same time be confident enough of his results to claim the

extra half grade, knowing what this implies. To keep the results similar to those of the C.R.G., the range of

gradings can be limited to any whole or half number between 1 and 7.

A point which arises from a study of table 1 is that

normally cave surveys should not be made using instruments that on the table

occupy more than two adjacent horizontal lines. If a wider range than this is used, then one of the instruments or

methods will be considerably more (or less) accurate than the others. Any such combination can give rise to a false

reading on the scheme.

The only originality, in this scheme is an attempt to

standardise a procedure that cave surveyors have been making ever since the

Cave Research Group first published their survey gradings – denoting on a cave

survey the appropriate grading when a method of survey was not identical with

one of the examples they gave. The

variations between the gradings given by this system and those originally

described by the C.R.G. are very small, and if this system were adopted there

would be no need to alter the gradings. I feel that this system is little, if any, more complicated than the

original but is definitely more consistent and more comprehensive.

I have now finished saying my little bit about the grading

of cave surveys, but I would like to hear other peoples reactions to my

thoughts. Possibly those of people with

experience of surveying would be the most enlightened, but this is not

necessarily so as all cavers look at surveys at some time or other. Now it is your turn.

B.M. Ellis.

November 1961.

Table 1

|

Instruments used |

|||||

|

Distance |

Direction |

Inclination and results taken into account |

|||

|

Estimated out of Est. noted in cave Pacing, counting Marked string, or

Cloth tape

Metal tape, Chain

Tachometer &c |

0.5 1.0 1.25

1.5 1.75

2.0

2.5 |

Estimated out of Est. noted in cave Hand held compass, Hand held |

0.5 1.0 1.5

1.75 |

Estimated out of cave Estimated and noted in cave Hand held clino, Hand held clino, readings to ± 1o |

0.25 0.5

1.0

1.25 |

|

If Leap-Frog method used with hand held |

|

||||

|

Calibrated prismatic compass and |

4.0 |

||||

|

Theodolite, astrocompass or similar, |

4.5 |

||||

|

Factor available SURVEY TABLE |

|||||

Table 2. Comparison

of Gradings

|

Method of Survey |

C.R.G. Grade. |

New System grade. |

|

Sketch plan from memory, not to scale. |

1 |

1 |

|

Sketch plan roughly to scale. No inst. used. Directions & distances |

2 |

1.5-2 |

|

Simple compass (± 5o) and marked string. |

3 |

3 |

|

Prismatic compass (± 1o) and cloth tape or marked string. |

4 |

3-0 – 3-5 |

|

Calibrated Pris. Comp. (± 0.55o) metal tape and clinometer. |

5 |

4-5 – 5-0 |

|

Tripod mounted prismatic compass (± 0.5o) Clinometer (± 0.55o) |

6 |

6 |

|

Theodolite, tachometer, metal tape. |

7 |

6.5 – 7-0 |

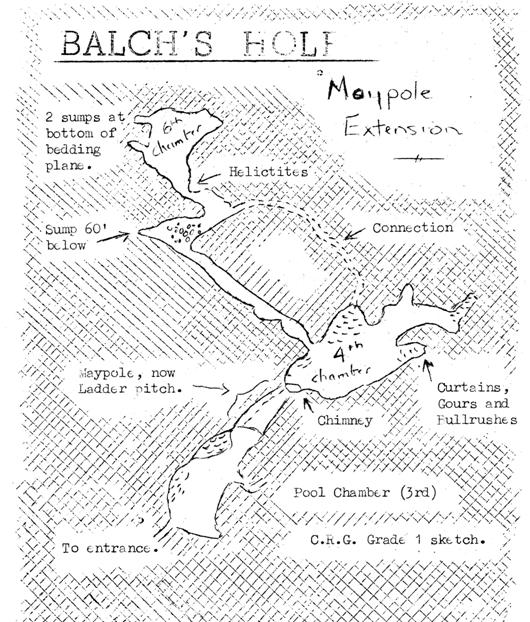

Balch’s Hole Extension

by Jill Rollason.

In January 1962, rumour had it that another 1,500 feet of

passage, thick with stal, had been discovered in Balch’s Hole after entry via a

maypole pitch and a trip was arranged for interested B.E.C. members – mainly,

photographers.

The extension is a high level passage, entered from Pool

Chamber. It is necessary to climb about

fifteen feet on the maypole ladder, and about a further fifteen feet up a steep

and difficult rift. At the head of the

rift is a narrow chimney about ten feet deep which leads into the FOURTH

CHAMBER, which is richly ornamented with white and cream flowstone, several

narrow curtains, and miscellaneous white stalactite. To the

right can be seen a slope covered with tiny peach-tinted gours and a fine

growth of red ”flowers” in a pool

– now dry but with remains of a false floor. The rock appears to be hardly more than compacted clay, and I was glad

to move to the next passage which has obviously been shaken in the distant past

(possibly by fault movement) but looked a little more reliable. Here there is a pillar-cum-boss about five

feet tall and two and a half foot in diameter which has been cracked into three

pieces and moved about a foot out of alignment. The break has not been caused by recent quarry blasting since new

stalagmites about four inches tall are growing in the old position.

The FIFTH CHAMBER,

which slopes at about 60 – 70° with a

steep boulder scree on the near side, leads to a sump about sixty feet below,

and the SIXTH CHAMBER which is angled at about fifty degrees and ends in a

bedding plane with two sumps at the bottom. Stalagmite formations are plentiful in both chambers.

I was a little disappointed with this series after the

enthusiastic reports which had been given, because I did not think it as

attractive as the rest of the cave, but the formations, which have been

compared, with those in September Series

in Cuthberts, are certainly well worth seeing.

It must be regretfully reported that within these few weeks

of the caves discovery, many straws have been broken and flowstone ruined by

mucky hands – all thoughtlessly and completely unnecessarily. It is impossible to blame anyone except

members of recognised, clubs, since; these are the only people who have been invited

to visit the place.

Note 1. The Maypole

has now been replaced by a fixed wood and wire ladder.

Note. 2. The water filled passage in Pool Chamber

described in the previous article has been tested by diving and proved to be

merely a pool.

The Belfry Bulletin. Secretary. R.J. Bagshaw, 699, Wells Rd,

Knowle ,

Bristol Editor, S.J. Collins, 33, Richmond Terrace, Clifton, Bristol 8.